The recent discovery of hundreds of children’s bodies at Kamloops Residential School confirms a heartbreaking reality for Indigenous people in Canada and provided a major break in efforts to solve a decades-old mystery for many of Canada’s Indigenous families with missing children. The dead include relatives of Grand Chief Ronald Derrickson.

Canada’s Residential School system was a nationwide effort by the Canadian Government Department of Indian Affairs to separate Indigenous children from their culture and assimilate them into the dominant Canadian culture. The schools were a network of boarding schools administered by the Catholic Church, the Anglican Church, and the Presbyterian Church. The system was founded with its first school in 1834 in Ontario and the last one was closed in 1996.

Why Residential Schools?

Conditions at the schools were frequently cruel, which matched the purpose behind the schools. In 1883, Prime Minister John Macdonald summarized that purpose, saying,

“…that Indian children should be withdrawn as much as possible from the parental influence, and the only way to do that would be to put them in central training industrial schools where they will acquire the habits and modes of thought of white men.”

In June 2021, Macdonald’s statue was removed from a major street corner in Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island.

Damage to Indigenous Children by Institutions

In 2015, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada released a detailed report resulting from eight years of investigation. According to the TRC, over 150,000 First Nation, Metis, and Inuit children went through 139 schools throughout Canada. Children were often malnourished, subjected to diseases such as influenza and tuberculosis, and were often victims of sexual or physical abuse. They were required to perform chores and often farm work. Conditions, including disease, resulted in over 3200 child deaths.

To the Derricksons and countless other First Nation families, this story is well beyond a government report filled with statistics and history. Tens of thousands survived these experiences as children, and while the residential schools are gone, the damage remains.

In 2008, Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper formally apologized on behalf of the Government of Canada. Meanwhile, none of the institutional churches who administered the schools ever apologized. Derrickson says,

“This is what is wrong with religion. The Pope and Archbishop have refused to apologize to the Indigenous people and their families for the abuse, torture and murder of young children and they deny responsibility for their participation in running residential schools.”

“…all names of people who worked in the residential schools should be published whether they are dead or alive.”

Life for Indigenous Children at Residential Schools

Derrickson himself was sent to residential schools and, along with Chief Arthur Manuel, authored Unsettling Canada: A National Wake Up Call. The book described Kamloops, saying that even for children who did not suffer extreme abuse, residential school experience was,

“…a time of great loneliness and alienation. The schools are cold places to spend your youth, and the staff worked diligently to reinforce in us a sense that in Canadian society, we were the bottom of the heap and were powerless to resist. They demanded, and rewarded, obedience. Nothing else.”

Derrickson further described the schools, specifically Omak in Washington, in Fight or Submit: Standing Tall in Two Worlds, a compelling book that is currently a finalist for a Forward Reviews award. He and his brother Noll Derriksan went to residential schools. After two years at a residential school the government mandated their attendance at a public school in Westbank, British Columbia. At the public school they were beaten on a daily basis. He joked that as a lighter-skinned brother, Noll was treated slightly better. At the age of five Ron was required to stand all day in the back of the classroom because there were no desks available for the “Indians”.

In this brief documentary, Derrickson tells the story of how Indigenous children were constantly told that education, and the opportunities that it afforded, wasn’t really for “the Indians”. The news of the residential school discoveries, “…reminded me why I still work so hard all day. I don’t ever want to feel poverty again.”

His daughter, award-winning musician Kelly Derrickson sang of the schools in the graphic All I See is Red. Kelly says,

“…the news of the Kamloops Residential School tragedy echoes far across Turtle Island at every residential school built to strip our people of their land, heritage, traditions and culture. We want justice!”

Grand Chief Derrickson’s Proposal

Derrickson says,

“Natives are extremely angry at the government and churches in Canada. Instead of waging a war we demand that the government of Canada seize these properties and give them back to victims and families.”

The Derricksons will mark Canada Day, “…an insult to the relatives of the victims of those murders” by honoring the victims of the residential schools and their families.

In the 2017 book The Reconciliation Manifesto: Recovering the Land, Rebuilding the Economy , Derrickson and Manuel guide the reader through the relationship between First Nation peoples and Canada. The book outlines steps to put the relationship on an honorable footing.

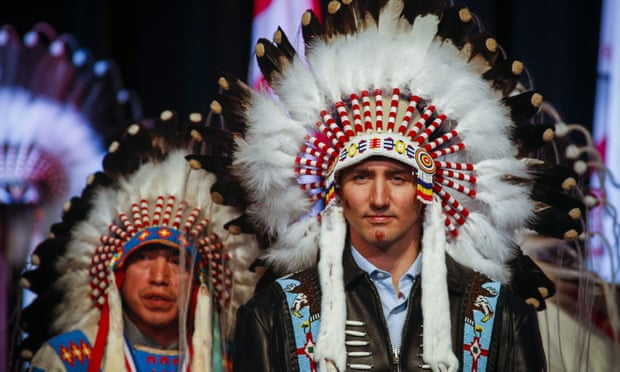

Chief Derrickson, like the people of the First Nation, strongly encourages Canada’s elected leadership to do more than occasionally show up to make a speech in ceremonial headdress.

In the spirit of reconciliation, Derrickson has sent a copy of Reconciliation Manifesto to Prime Minister Justin Trudeau.

Reconciliation Manifesto, along with many of Grand Chief Derrickson’s other relevant works, are available on Amazon. Educators and reporters are eligible for a free copy and should request one here.

The Kamloops discovery has sparked a needed national conversation. It is a painful conversation for families with members that survived Kamloops and other residential schools, as well as families whose children did not survive the schools. The families of many of the 215 bodies found at Kamloops may finally gain clarity and accountability. However, those families are far from the only ones.

Anyone experiencing pain or distress as a result of their residential school experience can access the 24-hour, toll-free and confidential National Indian Residential School Crisis Line at 1-866-925-4419.